It doesn’t matter what it says on the outside of your tombstone. What matters is what it says on the inside of your tombstone.

This is the career advice I received in 2006, as I was transitioning between my second career in bioethics and my third as a global health funder, from the late Dr. John Evans, a global health pioneer (among his other amazing accomplishments).

What he meant was that it isn’t your title that matters; it’s what you accomplish.

Rather than think of your career as your role, think about it as the series of successively important problems you’ve tackled and solved.

How do you find problems to solve?

The most important problems to solve are usually right in front of you. Just ask yourself: what irritates you the most? What is most outrageous? What is most unjust?

I remember clearly how I was drawn into the problem of end of life care. Forty years ago, when I was an intern making ward rounds with the attending physician, we were reviewing the case of a woman in her 30s with widespread cervical cancer who was in my care. She was dying. On rounds, I noticed that we discussed at length the many causes of low phosphorus level in her blood, but not whether to resuscitate her when she would, sadly and foreseeably, have a cardiac arrest. I found this outrageous and wanted to do something about it.

So I set about trying to improve end of life discussions and decisions. I designed a living will to help people plan the end of their lives, described the process of advance care planning, identified key parameters of quality end of life care, edited and co-authored a series of articles and a book for clinicians, and more.

I also made mistakes. For example, I surveyed nursing homes on their do-not resuscitate policies rather than working to improve the end of life care of the patients who died on the general internal medicine ward literally 20 feet from my office door.

The lesson I learned? Look immediately around you for the most important problems to solve. Tap into your lived experience.

Or even: turn your own personal experience of inequity or oppression into solutions for others. One of the people I have been privileged to meet recently is Samra Zafar. Her book, A Good Wife: Escaping The Life I Never Chose, is based on her personal journey of escaping an abusive child marriage to pursue her education, and shed light on gender-based oppression. She now advocates for equity, inclusion, and human rights.

In finding problems to solve, please remember: the biggest mistake you can make is not failing to solve an important problem that is right in front of you, but failing to try.

How do you go about solving problems?

Everyone has skills. Leverage yours. If you’re a molecular biologist, don’t volunteer to dig wells.

Dr. Dixon Chibanda leveraged his training as a psychiatrist, one of only a handful in Zimbabwe, and his local experience close to the problem, to develop the Friendship Bench, which provides sustainable community based psychological interventions that are evidence based, accessible and scalable. In 2022, the Friendship Bench provided free talk therapy delivered by grandmothers on a park bench to 94,000 people, and in 2023 plans to reach over 200,000 people. I feel proud to have been an early supporter through Grand Challenges Canada.

You don’t need 10 years of specialized training to solve problems. Often, the most inspiring problem solving is by young people. Take Vaccine Hunters Canada, a group of young people who teamed up to to connect eligible Canadians with vaccination appointments and get more shots in arms. At the height of COVID-19, they created a website where users enter their postal code for access to available vaccine appointments close to their location and associated eligibility information.

The key in solving problems is matching a particular problem to the methods most likely to solve it. I remember when I was a researcher hearing endless arguments about quantitative versus qualitative research methods. It was obvious that the choice depended on the question being asked (and often both methods were better than either alone).

How do you evaluate impact?

Most important in evaluating the impact of your work is mindset. Be honest and non-defensive. Early in my career, I was quite defensive, and this attitude held me back.

Don’t have a fear of failing. Embrace failure. Failure is good as long as its fast, cheap and you learn from it.

Early in my career, I wanted to see and talk about only success in my work. Now I know that every problem I tackle, if I am honest, results in both success and failure. And talking about it this way builds credibility and trust.

Over the past three years I have been working on the SDG3 Global Action Plan, which brings together 13 multilateral agencies to help countries accelerate progress on the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets, through strengthening collaboration among agencies in supporting national priorities. Is it a success or failure? It is both. Our focus this year is an honest stock taking of what worked, what didn’t, and how to move forward.

Don’t confuse failure with negative results (i.e. showing something doesn’t work). At Grand Challenges Canada, we understood the value of investments that produced convincing, negative results. For example, Dr Madhukar Pai’s research in 2011 on the inaccuracy and poor cost-effectiveness of then widely-used antibody tests for tuberculosis led to a “negative policy recommendation” by WHO. In other cases, convincing negative findings mean that others do not have to go down the same track and could focus on more productive lines of innovation.

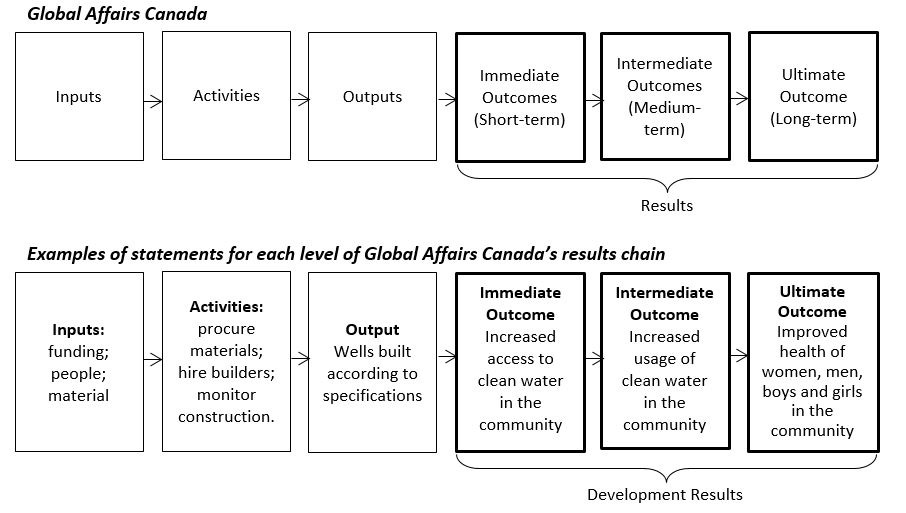

Beyond mindset, understanding results based management can help you to evaluate your impact. Below is how Global Affairs Canada shows its results chain (and we find a similar approach in the UN system). In evaluating impact you want to talk about both the results of what you did (called outputs below) and the impact that had on the people you seek to help (called ultimate outcomes below).

The trick is that you control the outputs (and they can be attributed to you) but usually others control the outcomes (and you only contribute to those). Although most people and organizations plan from left to right, I suggest that the way to have the biggest impact is to plan from right to left. Figure out the impact you want to achieve and then work backwards to what it takes to get there.

How do you tell your story (well)?

In job interviews, talk about how you found a problem and solved it. What was the problem? What did you do? What was the impact?

The more you solve problems, the better you will get at it and the more opportunity you will have to solve even more significant problems. To gain these greater opportunities it helps to tell people about what you have already accomplished.

In telling your story, make it personal. Why did you chose a particular problem to solve? Did you have first-hand experience of it?

Talk about both outputs (of what you did) and outcomes (especially impact on people). You need to link the two to show how your outputs led to the outcomes / impact. But remember: outputs are usually boring; outcomes and impact are inspiring.

Telling your story about how you found a problem and solved it is useful in all job interviews. It is especially so in competency based interviews such as those used by the United Nations and its agencies (like WHO).

Peer feedback is useful to improve your approach and how you describe it. When I speak in classes I often ask students to share with each other the problems they have tackled, what they did, and what was the impact.

It’s good to practice telling your story, until you tell it very, very well. You will know when you are at this point by when you inspire your listeners.

I invite you to tell your story about finding a problem and solving by leaving a comment below. And I invite other readers to comment on your story. (Or just say what you thought of this advice to find a problem and solve it.)

In short, to find a problem and solve it, be a social entrepreneur. My favorite definition of social entrepreneurship comes from Bill Drayton, the founder of Ashoka. He says, "Social entrepreneurs are not content just to give a fish or teach how to fish. They will not rest until they have revolutionized the fishing industry."

Next time, Part 2: Get the right mentors working for you.

In public health, it is quite easy to find shortcomings and offer advice. Everyone knows what is wrong but what that matters is what is done to solve the issue.

It is not possible to solve every issues by a single person, but all that matters is whether things are better than yesterday; "a justiciable justice" as told by Amarthya Sen.

Great article. I liked the use of logic models which I have been using and advocating for many years at CDC and WHO. It is true that we face challenges and learn from acting on them. It is important to take time to reflect on them. A self evaluation, I’d say. Thanks