The dirty little secret of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is there has been no progress, beyond keeping up with population growth, since 2015. UHC reports all say the same thing (but in a lot more detail!): about half the world has UHC, and we need to do better.

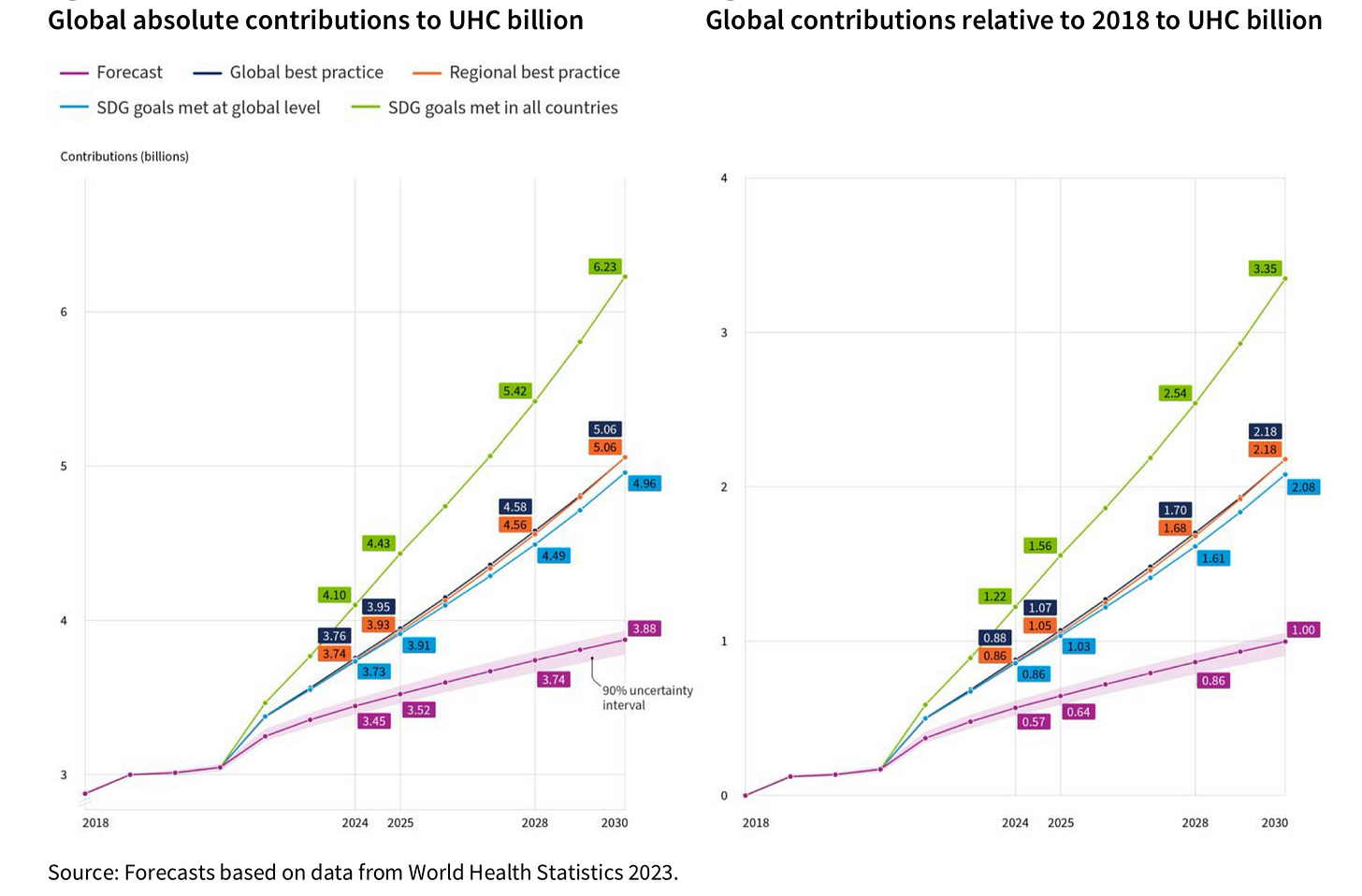

Here are projections on UHC, which is itself a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), to 2030. As you can see (purple line on the left), less than 4 billion people (less than half the world population in 2030) are forecast to benefit from UHC at current rates of progress.

We are more than half way through the SDG period of 2015-2030. Consequently, there is a very simple question we must ask ourselves: what will we do differently in the second half of the SDG period compared with the first half? How do we double the pace of progress?

The fundamentals

There is no better or more passionate description of UHC than that given by my brother Dr Tedros at the recent World Bank spring meetings. I think of this as UHC fundamentals. His call is inspiring. But also this narrative has been unchanged for several years and will not by itself double the pace of progress.

Four elephants

Twenty-two friends recently published an article in The Lancet identifying four “elephants in the room” which they saw as the barriers to progress on UHC. These were:

Political commitment

Inadequate and unsustainable financing for UHC

Fragmentation in global health governance, and

How advocates communicate about UHC.

They end their article with this commitment:

We are committed to working differently, and collectively, to achieve a step change in UHC between now and 2027. This requires acknowledging long-standing barriers to UHC and effectively tackling these roadblocks before haggling over downstream technicalities. To address the four elephants in the room that are hampering progress on UHC, we, as individuals with leadership roles in global health who are working on UHC, call on all stakeholders to hold political leaders accountable for tangible actions to advance their political commitments to UHC; to centre UHC in advocacy and action; to build coalitions for UHC beyond the health sector; to advocate for increased domestic financing for health and universal social protection; and to develop and align around a UHC roadmap that addresses key drivers and enablers of UHC and clearly identifies which organisations or entities have responsibility for which part of the work.

I applaud their approach and admire their commitment. All the things they identify should be done. In fact, many of them are already being tried through multiple High-Level Meetings at UN General Assembly, SDG 3 Global Action Plan and Future for Global Health Initiative / Lusaka Agenda, WHO’s Primary Health Care Special Programme, WHO/Multilateral Development Banks’ Health Impact Investment Platform, and UHC 2030 (which recently released its strategic framework based on advocacy, accountability and alignment). All of these are very worthwhile but I don’t think they will double the pace of progress without much more robust implementation.

Getting Shit Done

So how then to double the pace of progress? I propose an approach I call GSD (Get Shit Done). This approach has three key elements: results-based governance; delivery for impact; and scaling innovation. (For regular readers of my blog, this post applies the GSD approach to a single concrete issue (UHC), for the first time.

Results-based governance: The governing bodies (and leadership) of multilateral agencies like WHO and World Bank can bring greater accountability to UHC. One would start with bold targets, which provide focus, inspire action, and enable accountability. In an earlier blog, I outlined what a more results focused Executive Board meeting at WHO would look like. The Board would start with the overall progress on UHC (which is the responsibility of countries), against a bold target, as shown in the chart at the beginning of this blog. WHO set an SDG-based target of 1 billion more people with UHC between 2018 and 2023 (later extended to 2025). As you can see from the chart above (right panel, purple line), it would actually take until 2030 to achieve this target at the current rate of progress! However, if all countries progressed at the rate of regional or global best practice, the world would have reached this target by 2025. Recently, the World Bank announced a comparable target of 1.5 billion people with access to health care by 2030 (which correlates closely with the regional/global best practice on the orange and blue lines for relative contribution between 2023 and 2030 on the right hand panel of the chart above).

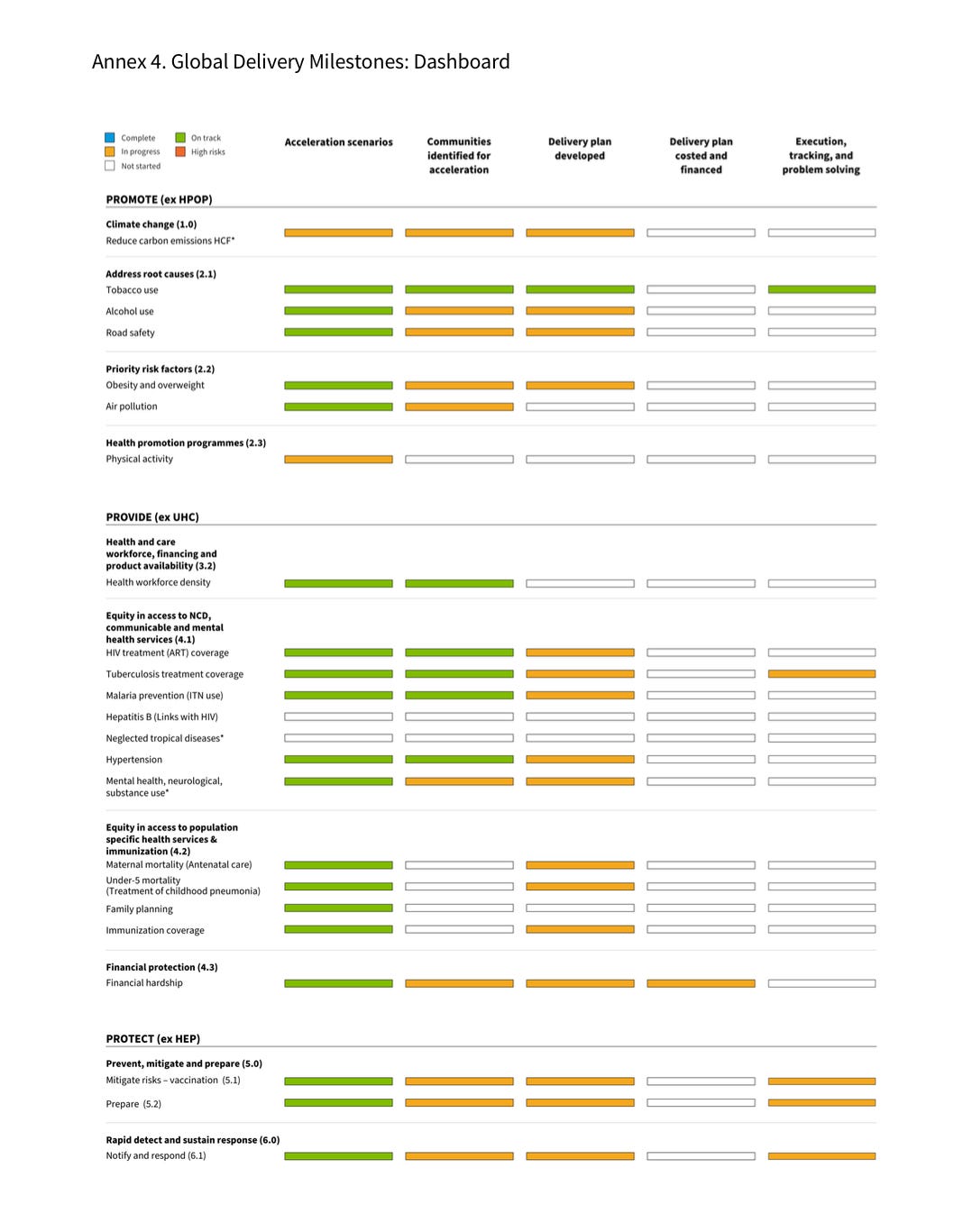

Because the UHC target is primarily the responsibility of countries, the WHO Executive Board (or governing body of any other multilateral agency using the same approach) could then examine what the Secretariat is doing to support countries on UHC, using a limited number of priority indicators based on the Organization’s comparative advantage and directly related to SDG targets (see middle panel on “Provide” below):

Governing for results is arguably the most important element of the GSD approach because all else flows from governance.

Delivery for impact: For each prioritized target (the rows above), the dashboard shows the WHO Secretariat’s performance on outputs that drive the target like:

Do we know the best practices on acceleration?

Has sufficient budget been allocated in the organization and in the country to drive progress?

Have specific high burden countries been chosen to focus on?

Have delivery plans been developed which identify specific normative guidelines or innovations to scale?

Is the organization supporting the government to track progress on the target and take stock on a regular basis?

Barriers to progress could be identified, and governance could support management to overcome them.

Ultimately delivering results happens at the country level. Individual countries track their progress on SDG targets underlying UHC (first chart, middle panel) and identify priorities for execution (second chart, country delivery dashboard) as shown below:

The main benefit of delivery for impact is it focuses more on supporting implementation over planning, a shift that is very much needed in multilateral organizations, which suffer from ‘planning disease.’

Scaling Innovation: Innovation spans products, services, digital, and finance, and often integrates all these elements, as we learned in the early days of Grand Challenges Canada. All these approaches can contribute to speeding up progress toward the SDGs, but for UHC new models of service delivery are perhaps the most useful.

Sometimes these service delivery innovations will be about Primary Health Care as in the case of Sehat Kehani, a virtual clinic in Pakistan that mobilizes women physicians to provide “a one-stop telemedicine solution.” Sometimes they will target equity-deserving populations as in the case of North Star Alliance, which establishes primary health care “Blue Box” clinics along trucking routes in Southern Africa, providing reproductive health services to sex workers and others. Sometimes they will target highly constrained services, such as Friendship Bench in Zimbabwe (using grandmothers) or SEEK GSP in Uganda (using patient groups) to address the shortage of skilled mental health workers. Sometimes they use digital solutions for specific services like ECG diagnostics and cardiac care pathways like Tricog Health, or for supply chain of health products such as Figorr. Sometimes they address data gaps like DHIS 2, an open-source platform used by more than 80 countries for collecting and analyzing health data, and improving performance of care. And sometimes they focus on innovative finance like the Health Impact Investment Platform.

These innovations are reaching tens or hundreds of thousands of people (or even millions), but need to be scaled up to tens or hundreds of millions to move the SDGs. That is where multilateral organizations could really help, including through ‘horizontal’ scaling across countries.

Getting started on Getting Shit Done

When I write about Getting Shit Done, I am sometimes accused of flogging a dead horse. I appreciate these critiques (and this commentator’s longstanding commitment to country-led development):

Certainly, the primary responsibility and power to make change lies with countries. And as my friends Muhammad Pate and Senait Fisseha brilliantly illustrated on a recent World Bank panel, a new public health order led by countries is emerging and will make progress. Also, geopolitics is getting tougher: I don’t think countries would be able to reach agreement now on SDGs, which is all the more reason to execute better on what they have already agreed!

When you look at the elements of the GSD approach, there is certainly scope for WHO to help these elements scale horizontally across countries. No other organization touches all 194 countries in the world on UHC with such breadth and depth. WHO could also have an important role in coordinate international organizations on UHC using data as demonstrated by the SDG 3 Global Action Plan (see here, pp 11-15). What I learned at WHO is that it’s tough to get something done, but once done it happens at scale.

There is resistance to accountability for results: results are hard, talk is fun, and people hate accountability. I have seen it in various organizations as the constant bureaucratic undermining of results based management and governance. We need to directly confront this resistance to overcome it. It is at a time of leadership transition that the greatest opportunity for change exists, as we saw with Dr Tedros visionary leadership. This is the case both in the top leadership of international organizations and of countries that bear ultimate responsibility for the health of their own citizens and the governance of international organizations.

Is there a group of countries (governments) that are sufficiently committed to results to demand better accountability from themselves and from international organizations like WHO? At the upcoming World Health Assembly, the ultimate governing body of WHO, will someone get up and say:

‘Hey! There’s been no global progress on UHC since 2015. What’s going on? How can we do better?’

I hope so. Let’s see.