The global health architecture is like an orchestra; but it’s not playing in tune.

More than a dozen multilateral agencies (with lots of acronyms) work in health — including UN agencies (WHO, UNICEF, UNAIDS, UNFPA, UN Women, WFP, ILO, UNDP), funds (Gavi, Global Fund, World Bank/GFF, Pandemic Fund, UNITAID), and product development partnerships (CEPI, MMV, DNDi, GARDP, IAVI, etc). Civil society, the private sector, philanthropic foundations, and academia all play a key role.

Fragmentation costs money and diminishes effectiveness — although its hard to find precise estimates. In a time of shrinking resources, it makes sense to make sure these groups work together in an effective and efficient manner.

There are incentives for agencies to collaborate — or give the appearance of doing so — but only to a point. Then the desire for promoting their own brand and raising funds kicks in. And some competition is healthy — if it's based on performance.

But if there was ever a time to improve collaboration, its now — when resources are scare and the entire global health ecosystem is being disrupted in fundamental ways.

Over the past 15 years, three major initiatives have tried to improve the global health architecture: IHP+, SDG3 Global Action Plan (GAP), and the Lusaka Agenda.

All these have some version of these three goals: strengthen primary health care; strengthen country leadership and domestic finance; better coordinate the multilateral agencies.

Each initiative tends to become the flavour of the month (or 3 years), weakening the earlier one, without really building upon it.

And yet each has unique lessons that should be combined. IHP+ promoted Universal Health Coverage and showed the value of country-based teams. SDG3 GAP showed the value of ongoing monitoring. The Lusaka agenda showed the value of leveraging the funds and elevating country demand.

I was the executive lead on SDG3 GAP. Here is what I learned — and how it can apply going forward.

Structural changes like merging or closing agencies could only happen from outside the agencies. They are never popular. I don’t know of any UN agency that has been closed.

One current candidate would be UNAIDS. It tackles a single disease which doesn’t even make it into the top 10 causes of death and whose incidence is falling. UNAIDS’ work overlaps with at least three other multilateral agencies and it doesn’t always seem to focus exclusively on HIV any more. The agency is drawing down its reserves for restructuring. A tough thought experiment: would the UNAIDS annual operating budget save more lives by using it to purchase Lenacapavir?

UNAIDS has a storied history, its early leaders are legends, and the agency played a key role in galvanizing the early AIDS response when others were failing. I have met many excellent people working at UNAIDS, and some of its leaders have been friends. But perhaps it’s time to declare success?

Another structural change could be to integrate Gavi and Global Fund into regional political bodies (such as the African Union) over a 10 year period. Such integration could be linked to regional manufacturing and public health. The regional Gavi and Global Fund “nodes” could be networked globally but not part of the same organizational structure. These agencies have achieved amazing life-saving results, but such integration might make their long-term funding more sustainable based on regional political ties. It would bring the financing closer to the political accountability. This would only make sense if their results could be preserved or increased compared to the agencies’ current trajectories.

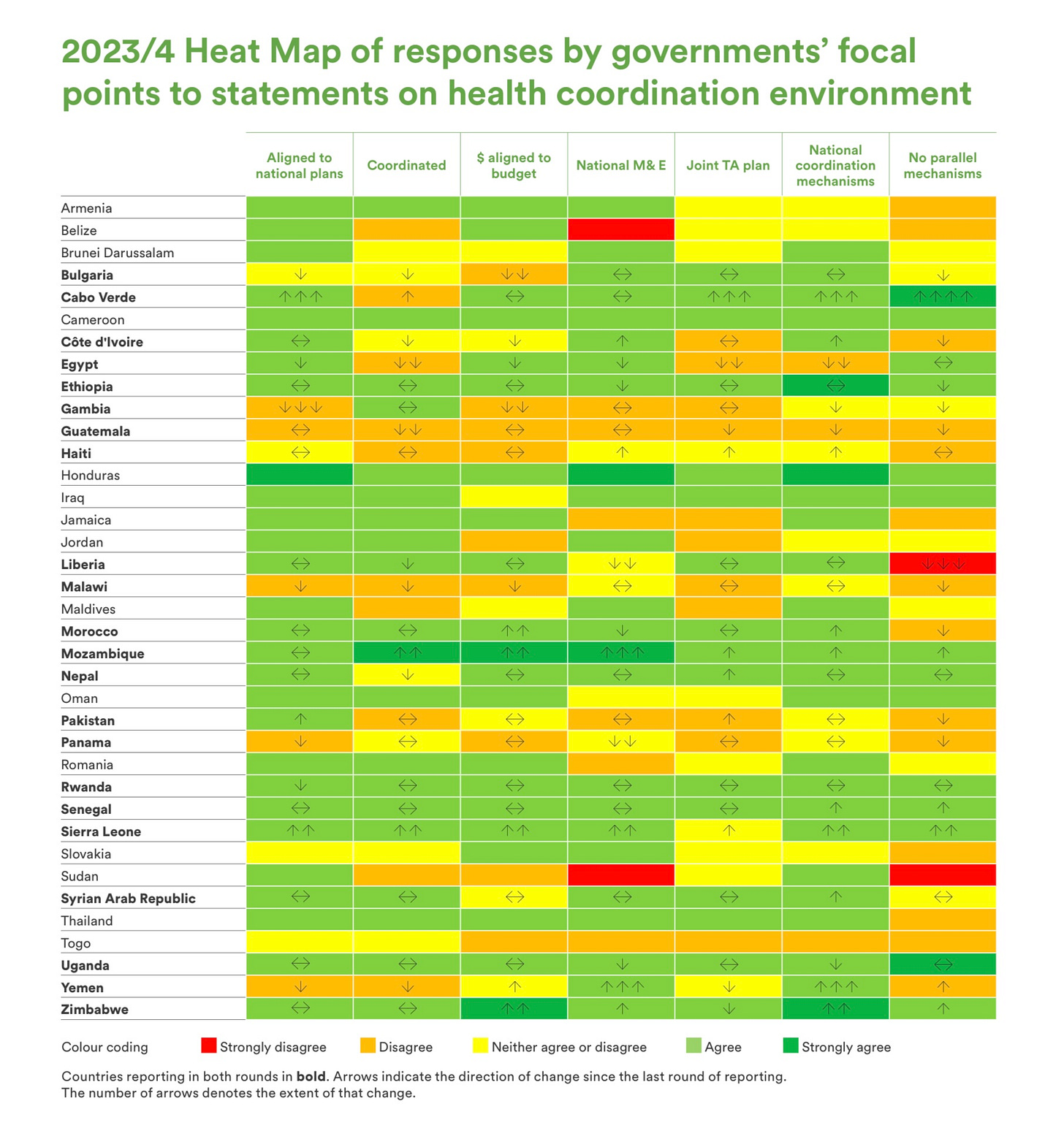

Functional alignment could be improved through ongoing monitoring. In SDG3 GAP we developed a survey completed by the top public official in health in countries asking how well multilaterals followed country priorities and how well they coordinated with each other. Qualitative comments were received about specific agencies in specific countries. It was like the ‘Consumer Reports’ of the multilateral system. The original idea came from the great Tore Godal, who reasoned that the agencies rate the countries; why not have the countries rate the agencies? We conducted the survey twice.

The resulting heat map could have informed agency boards but was never systematically presented to the boards or taken up. The agencies’ top management and boards currently lack incentives to do so. The survey should be resurrected but in a way that is integrated into board discussions and decisions. This kind of feedback loop could drive real change in agency behaviour.

The funds provide a unique leverage point. This is where the Lusaka agenda focused. It laid out principles, much like the commonalities among the initiatives outlined above. In June 2024 it also outlined specific next steps on implementation: joint work, joint oversight, cross-board collaboration, country implementation, and a joint vision for R&D, manufacturing, and market shaping. Without ongoing monitoring, it would be hard to tell how these are going. However, such accountability mechanisms are now being developed through Africa CDC and WHO AFRO regional office.

Most recently, the Wellcome Trust is commissioning five regional dialogues on the global health architecture. This will provide a forum for ongoing discussion. It’s an opportunity to combine the lessons of the earlier initiatives.

It’s too early to know what it will yield, but I hope it leads to action. Perhaps it could lead to structural changes. But at a minimum its should lead to better functional alignment. It’s worth thinking about both structure and function — there is a reason we have both anatomy and physiology.

Here is my proposal: use the SDG3 GAP survey to create a country-facing accountability system for global health initiatives. Also provide incentives for agency boards to hold themselves accountable for how they work together and serve country priorities. And create incentives for countries to play their sovereign role (e.g. “one plan, one budget, one report”), as some now do.

This can only be accomplished through the ‘push’ of donors and the ‘pull’ of countries. Collaboration needs to be concretized through management and governance mechanisms. SDG3 GAP piloted and proposed a path to scale for incentive mechanisms in joint funding, monitoring, evaluation, and governance.

Because of the inclusive governance of WHO — at least as far as member states are concerned — it is a natural starting point for coordination. The first function in its Constitution is “to act as the directing and co-ordinating authority on international health work.” But WHO must become more results-based to be effective in this role — and the disruptions it is currently experiencing do not seem to be favouring that. Regional member state organizations (and WHO’s regional offices) could also play an important governance role.

Any reform of the global health architecture must take into account how to connect the structure and process of the global health system to results. Does it reduce preventable death? Does it improve universal health coverage? Does it accelerate the fall in under-five child deaths? These are the acid test questions.

WHO has piloted a method called delivery for impact to link the outputs of agencies to these outcomes. Delivery dashboards have been developed and implemented around country priorities in 50 countries. These dashboards could serve to coordinate and jointly monitor agencies’ progress in supporting countries to reach their goals.

Reform must also reposition the global health system for the future — which will be country-led, results-driven, innovation-powered, and productivity-enhancing. As I wrote recently, the future of global health is innovation.

Accordingly, the global health system should be better set up to scale innovations. Here, closer collaboration with innovation funders would help — and not just UNITAID (although including it) because it is seen as a multilateral agency itself. The funders have pipelines of innovations and multilaterals operate at scale across countries. The goal should be to identify innovations that have already reached one million people and integrate them into country health systems so they scale to reach tens or hundreds of millions. A recent example is collaboration between Gavi and Grand Challenges Canada in launching an innovation fund to scale immunization solutions.

Finally, any reform must address the greatest fracture in the global health system — the exit from global health by the US. The biggest risk to the global health architecture is being pulled between two poles: one multilateral system for the BRICS and another for the US and countries that follow its lead.

In the face of the fundamental transformation underway in global health, it’s time to ask again about this orchestra: who is the conductor? Who is the audience? How do we get the global health orchestra to play in harmony?

Global Health Architecture

The analogy with an orchestra is a good one and can be developed further. When we attend our local music hall and listen to a musical masterpiece we are witnessing the talents and commitments of many contributors who come together to present the perfect symphony, opera or ballet. In relation to Global Health, the audience is the millions of people worldwide who expect to receive the best possible healthcare. Continuing the orchestra analogy, they will want to know who composed the music, who is conducting the orchestra, and how all the musicians and their instruments have collectively delivered a perfect performance.

Sadly, Global Infant Feeding Policy does not provide a perfect performance and serves as an example of a dictatorial non-functioning orchestra. Briefly, here are some examples.

In 2023 WHO arranged a meeting described as the first Global Congress on the implementation of the 1981 International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. Unfortunately, at this long awaited review, WHO and UNICEF “selected” and “vetted” delegates to ensure they did not have a conflict of interest, especially “ties” with industry and some delegates were subsequently disinvited [1]. Does this filtering of opinion reflect the principles of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and in particular the importance of non-discrimination and the right to be heard? It is noted that the introductory presentation was delivered by the Director-General of WHO.

The 2023 WHO Guideline for Complementary Feeding was heavily criticised in a joint publication from several health related societies and a key concern was the lack of consultation [2,3]. The WHO response to this concern was that “The societies… object to the fact that the guidelines were not subject to an open consultation process before publication. Public comment is not a usual practice for WHO guidelines and poses significant challenges for managing conflicts of interest, particularly on guidelines with implications for the sale of commercial products” [4]. This dismissal of the need for public consultation is discriminatory and appears to reflect a failure or unwillingness to manage differences of opinion. It is noted in the WHO Handbook for Guideline Development 2nd ed. 2014, that “Standard guidelines usually take between 9 and 24 months to complete, depending on their scope, and should be prepared after wide consultation on their need, scope and rationale”.

In 2023 a systematic review that was commissioned by WHO as part of the complementary feeding guideline, reported that there were no significant additional health benefits for the infant or for the mother from breastfeeding beyond12 months [2]. This conclusion was also reached by the Scientific Advisory Committee for Nutrition that advises the United Kingdom government [5]. However, despite this confirmatory evidence the WHO Complementary Feeding Guideline reaffirmed the view that breastfeeding for 2 years or beyond is a strong WHO recommendation and this was despite their acknowledgment that the evidence was graded as very low certainty [2]. Do governments and therefore parents act in accordance with WHO assertions or should they choose the scientific evidence? In this debate where is the governance perspective? Does the WHO complementary feeding document meet the UNCRC principles? Or does it reflect self-interest and lack of transparency?

In the 2023 complementary feeding document WHO also recommended that infants who are not being breastfed may be commenced on cow’s milk at 6 months, despite well documented health concerns relating to the introduction of cow’s milk in the first year of life which include iron deficiency, anaemia and gastrointestinal blood loss. [2] No new evidence was provided to support this change in policy. The clinical presentation of an infant passing blood is one that must always be taken seriously as it may be heralding a life threatening clinical condition. Is this an attempt to limit the infant formula market at the expense of the health of infants and the expressed wish from parents that they have an official safety net for lactation failure?

It is concluded that infant feeding remains a contentious global issue. The UNCRC is an essential document for ensuring that parents and their children are protected and supported. Current global infant feeding policy documents do not meet the principles or the spirit of UNCRC and therefore do not merit legislative status. An independent review is urgently required with the objective of providing a global policy/architecture for infant and young child feeding. With there now being a deep seated mistrust between infant feeding stakeholders a new approach should recognise that trust is not only a fundamental principle for change but it is also a fundamental right for infants and their parents.

Returning to the orchestra, the architecture of this particular global health responsibility lacks independent composers, inclusive conductors, an appropriate range of musicians and their instruments, and an appreciative audience.

References

1. WHO. Global Congress on implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/global-congress-on-implementation-of-the-international-code-of-marketing-of-breast-milk-substitutes

2. WHO Guideline for complementary feeding of infants and young children 6–23 months of age. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

3. European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology & Nutrition(ESPGHAN), European Academy of Paediatrics(EAP), European Society for Paediatric Research(ESPR), et al. World Health Organization (WHO)guideline on the complementary feeding of infants and young children aged 6−23 months 2023: a multisociety response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.2024;1‐8. doi:10.1002/jpn3.122488

4. Grummer-Strawn LM, Lutter CK, Siegfried N, Rogers LM, Alsumaie M, Aryeetey R, Baye K, Bhandari N, Dewey KG, Gupta A, Iannotti L, Pérez-Escamilla R, de Castro IRR, Wieringa FT, Yang Z. Response to: World Health Organization (WHO) guideline on the complementary feeding of infants and young children aged 6-23 months 2023: A multisociety response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2024 Nov;79(5):1084-1086. doi: 10.1002/jpn3.12363. Epub 2024 Sep 12. PMID: 39263990.

5. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. Feeding young children aged 1-5 years. London. Gov.UK; 2023 https://www.gov.uk/government/groups/scientific-advisory-committee-on-nutrition

Your key point - "Any reform of the global health architecture must take into account how to connect the structure and process of the global health system to results." What would drive this, I presume, would be a coalition of national decision makers that would work to carry this out for at least this coalition subset. Alan