Improving global governance to Get Sh*t Done (GSD) on the SDGs

You have heard of the G7 and the G20. But what is the G194? For health, that is WHO, which is governed by 194 countries.

Before I came to work at WHO, I used to think this governance structure made WHO inefficient and ineffective. In some ways, it does. But this governance also makes WHO legitimate. There are many other organizations in global health. But none can claim this legitimacy. This governance legitimacy could be improved and leveraged to speed up the SDGs.

In 2015 the governments of the world agreed to a set of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Of 169 targets, around 50 are health-related. But at the midpoint, they are badly lagging. Only 15% of SDGs overall are on track and the over-arching goal of Universal Health Coverage is going at less than half the pace needed to reach the 2030 targets.

In my previous blogs, I have written about “how” to speed up SDGs — which I call the GSD (Get Sh*t Done) approach — through leadership and partnership, data and delivery, and digital and innovation. Using the example of WHO, I have shown how under Dr Tedros’ leadership the measurement and management of SDGs has improved. Because countries are primarily responsible for SGDs, the key focus of this work is at the country level. To be sustainable, however, the measurement and management of SDGs must be embedded in and incentivized by governance.

In this blog, therefore, I focus on global governance for impact. I show how WHO could improve its own governance accountability, both within WHO and across the global health ecosystem. By doing so, health could serve as a pathfinder of how the UN and broader development system could improve global governance to Get Sh*t Done and reach the SDGs — all in support of countries, which have the primary responsibility to achieve the SDGs. The September 2024 Summit of the Future provides an opportunity to promote results-based multilateralism.

In short, better global health governance can Get Sh*t Done (GSD) to speed up the SDGs.

Improving WHO’s governance

Synthesizing a widely-used model of non-profit governance, we could say that governing bodies have four key functions: hiring and firing the chief executive, setting the strategy of the organization and measuring progress against strategy, defining the limitations beyond which management must not go, and evaluating themselves. In the multilateral setting, a key fifth function would be negotiating and approving international treaties and regulations.

WHO governance does four of these five functions pretty well. It reformed its method of selection of the Director General before Dr Tedros election so each country has one vote. It puts great emphasis of financial accountability and prevention of sexual exploitation, harassment and abuse. It created a group to strengthen governance. And it is in the midst of negotiating a pandemic accord and revising the International Health Regulations.

On strategy, WHO governance is good at setting strategy but weak at using measures of progress against strategy to guide its discussions and decisions.

Under the 13th General Programme of Work the Secretariat tried to close this gap through the use of “Output Score Cards”, which were based on the Balanced Score Card approach of Kaplan and Norton. A key advantage of this approach over the pre-existing heterogeneity of outputs was coherence: accountability measurements was all on the same scale making it much easier to understand. However, as noted recently by WHO’s Executive Board itself, the outputs are not directly linked to SDG outcomes. To address this, for some time now, the Secretariat has been pioneering a new approach to accountability using delivery for impact.

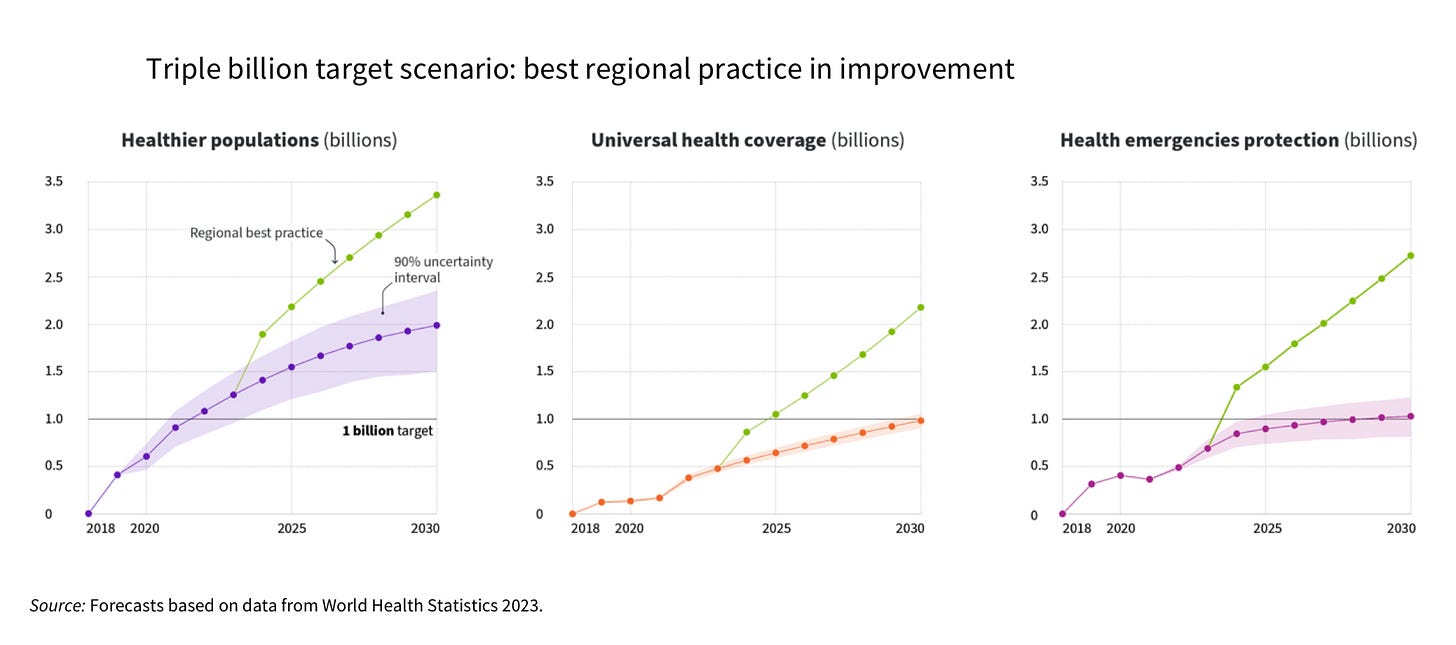

Imagine a governing body meeting that starts with countries’ progress on key SDGs, grouped into the “Triple Billion” targets of Healthier Populations, Universal Health Coverage, and Health Emergencies. These targets can be related to the progress needed to reach the SDGs or regional best practices, as shown below:

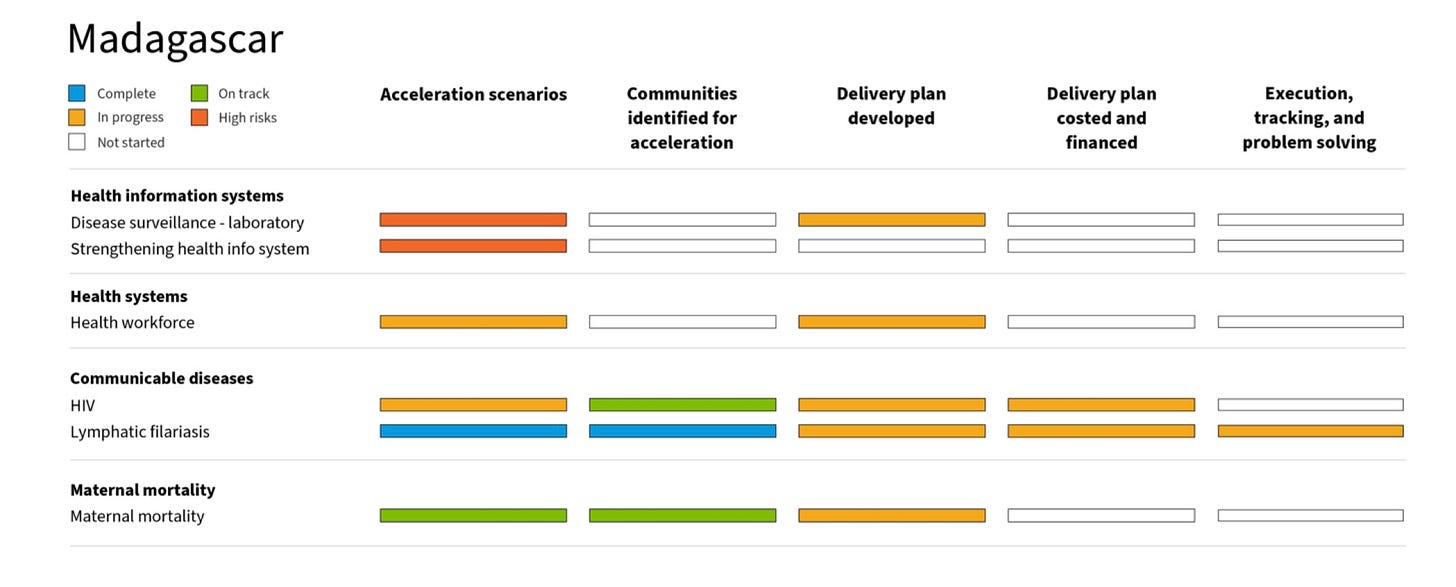

Then, it could take a deeper look at individual SDG targets in specific countries, as shown in the figure below:

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the governing body could explore the Secretariat’s contribution to supporting countries on these SDG indicators. Of the 50 or so health-related SDG indicators, about half are very much within WHO’s comparative advantage to lead in helping countries implement. Below is a example with 5 selected priorities grouped by billion (a more complete version of this dashboard with ~ 25 global priorities is available):

For each prioritized SDG target, the dashboard shows performance on questions like: Do we know the best practices on acceleration? Has sufficient budget been allocated in the organization and in the country to drive progress? Have specific high burden countries been chosen to focus on? Have delivery plans been developed which identify specific normative guidelines or innovations to scale? Is the organization supporting the government to track progress on the target and take stock on a regular basis? Barriers to progress could be identified, and governance could support management to overcome them.

Improving governance across the global health ecosystem

Although WHO is at the centre of global health governance, many institutions contribute to the achievement of health related SDGs. But they don’t always work in concert. How could governance across the global health ecosystem drive SDG progress?

This was exactly the question addressed by the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well Being. Its 2023 progress report was a honest look at the multilateral system and contained some clear recommendations. (Disclosure: I was the Executive Lead at WHO responsible for this report while I was there.)

Three recommendations in particular stand out. One was directly related to governance:

strengthen incentives for collaboration through stronger political leadership, governance direction and funding for collaboration.

Although many partners contribute to supporting governments at the country level, the governing bodies of these agencies do not often focus on how they work jointly with other organizations. There is in fact both collaboration and competition as each builds its brand and funding base. The Global Action Plan did some experiments to provide data on collaboration to agency boards. A video case study example from the UNICEF Executive Board is here. This could be built upon with a standing item on the agendas of all boards related to collaboration.

Another recommendation aimed to provide empirical data to focus these governance discussions.

Further strengthen the SDG3 GAP improvement cycle for health in the multilateral system

See this survey of governments regarding how well multilateral agencies collaborate to support them. This type of survey data can be used to improve collaboration.

But what about linking the process of collaboration to SDG outcomes? This recommendation aims to provide a results-based common language which could inform governance:

Jointly apply new approaches at country level such as delivery for impact;

Imagine if the collaboration among agencies in support of countries was around country-selected priorities as shown below:

Each agency could agree on its role — who does what — similar to the ‘one plan, one budget, one report’ approach that has proven successful in countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda.

Summit of the Future

In September 2024 the UN will host the Summit of the Future. The description of the Summit reads as though it is the perfect opportunity to introduce better governance for impact across the UN system:

Given the turbulent geopolitical environment now and for the foreseeable future, our emphasis should be on implementing the ambitious agreements that have already been negotiated, rather than proposing new plans, strategies, and reforms. Let’s execute better on what we have already promised. Let’s take a GSD (Get Sh*t Done) approach to the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals). That means focusing on execution (over planning), data and delivery (over inputs), and innovation (over status quo). I don’t think the GSD (Get Sh*t Done) approach eliminates the spoiler risk of geopolitics, but I do think that it could mitigate geopolitical risk and that results provide a new foundation for trust in the multilateral system.

The Summit of the Future provides an opportunity to advance results-based multilateralism. The draft “Pact for the Future”, which will come out of the Summit, does not do that yet. However, in summarizing an informal consultation, the Namibian co-facilitator (the other co-facilitator is Germany) said they would bring back a more “pragmatic” version. So there is still hope. Of course the key is not what it says in the resolution, but what the multilateral institutions actually do — and that requires leadership on their boards.

UN agencies cover most or all SDGs and can be mapped against them. They should be accountable not only for measuring progress against SDG targets (which they already do as “custodians”) but also for managing their contribution toward supporting countries to reach those targets. At the moment there is a disconnect between progress against SDG targets and agency accountability. SDG progress and agency accountability need to be more closely connected. Everything else above flows from this premise. This is results-based multilateralism.

Can you imagine a company losing money year after year and the board ignoring it? One radical suggestion: the agency’s contribution towards supporting country SDG progress could be an element of performance evaluation (or reappointment) of the head of the agency. I am not the first to suggest this.

The problem is we haven’t really had a way of measuring the agency’s contribution to SDG progress, which is primarily a national responsibility. But using delivery for impact and delivery dashboards, WHO has now developed and tested a way to measure and manage Secretariat contribution (outputs) in a way that is connected to SDG outcomes. By measuring and managing their contribution towards SDG outcomes, multilaterals build trust. And this should be a key focus of their governance. Indeed, this recent statement from the Secretary-General makes this same point.

This is what I mean by results-based multilateralism — or more colloquially, Getting Sh*t Done (GSD) on the SDGs. But to do it, we have to actually do it. Better governance for impact of our multilateral agencies is how to do it, and the Summit of the Future is the opportunity to embed results-based multilateralism within UN agencies.